In these times, Bill, it seems to me that for arts organizations, uncertainty and hope are in a standoff.

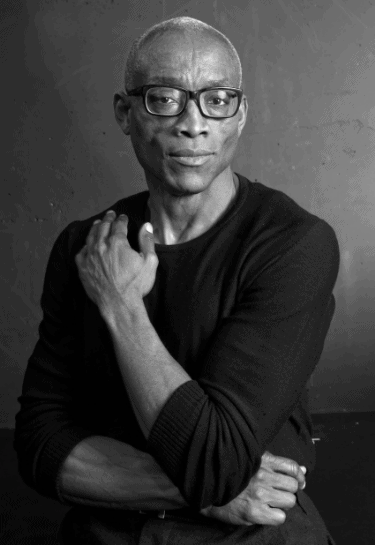

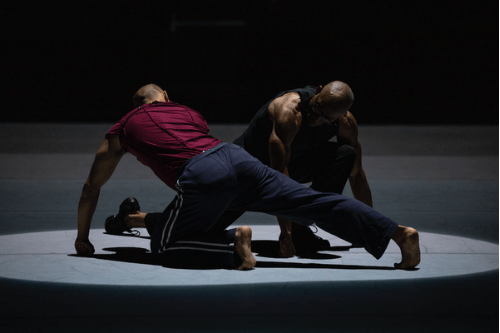

Very well put. Uncertainty. You know, when I was doing a work a few years ago at the Kennedy Center, someone asked me: What has been an element that has not changed in your work, Mr. Jones? And I said: Doubt. It burns like fire. So I live with doubt. Is doubt the same as uncertainty? Well, they are related. The uncertainty is: When will we be able to do what we do in the same room again? That has been debilitating. And it has taken a lot of faith and hope – and it has taken Kim saying, “This will pass.” And Janet saying: “Let’s not sit and wring our hands about the work we have lost or what we don’t know. Let’s just keep doing right now.” So, let’s show how nimble we are. We’ve seen it in the field – this pivoting, this going digital, which I have, like a lot of people, both cursed and have been thankful for. It is an example of hope. We’re not going to stop our work. We’re not going to stop dancing. But we have to find another way to do it. What do I know having survived the HIV-AIDS plague and now to be in this one, and looking at an uncertain election? There’s something about hope and determination, and grit, that comes into it.

What does that hope mean for you?

I’m a man who is almost 70 years old. Artists like myself say: We don’t retire. We just adapt to a new reality. So nonchalance is now an act of faith, faith that I am going to do this work and that I am going to move forward as if I will be touring again with the company. I’m going to move forward as if these young dancers coming in will be provided with a salary, and we’re still programming New York Live Arts as if we are going to be here. We want to make ourselves even more useful to the community. So that is hopefulness. There is a community. It’s changing, and we want to be participants in it.

I’ve been talking to you or observing your work over the course of 30 years. Each time, I have heard your anger and your hope. And today I hear your hope, and I have to say: It surprises me. I thought I might get you at your most angry today.

Well, stay tuned. [Laughter.] I want to say something reflexive and glib, like I have no choice. I have so much to be grateful for. I have an organization. I have my company. I’m being interviewed by APAP about my take on things. What do you do with that? You have to stand up stronger. At least I have to. Now does that come from parents and their struggles? Maybe. I can tell you, I feel a great privilege and responsibility to have been able to keep our staff on salary. We have a board that is committed. We had really gotten our house in order. I do have my moments, but I am trying to understand what maturity is. Maybe that’s the word, isn’t it? Either way, it takes something like a positive stance. One has to say: I own the place I’m standing, and I’m not afraid of what’s coming. That looks like hope, looks like resolve.

You once said to me that you love this country and when I asked you why, you said dreams can still happen here. How are you feeling about that now?

I come from the lowest classes in the country. We were migrant workers. My dad lost everything. My mother and father, they had all their dreams from 1948 until they lost their house somewhere in the late ‘60s or early ‘70s. But I have been able to do this thing called contemporary performance, dance. It wasn’t just an accident. Maya Angelou used to say: You all go on. If you’re Irish, if your Italian, if you’re Black, if you’re Chinese, you have been paid for. Go on. Go for it. I still hold on to that belief.